Trying to learn about spirituality through reading

Three books from Carribean authors touching on spirituality

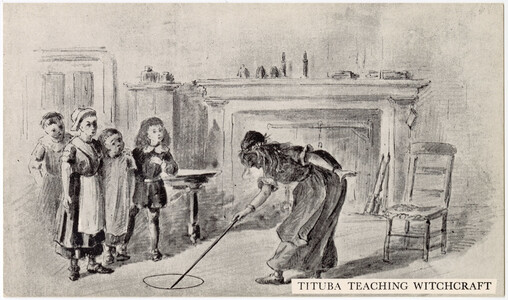

Bestimmte Rechte vorbehalten von Salem State Archives

Recently I read two novels and an autobiography by authors from the Caribbean. Originally I was interested in topics around spirituality and women’s liberation and that is why I started with the novel Tituba, black witch of Salem by Maryse Condé. It is the imaginary biography of the only black woman that was targeted in the infamous New England Salem witch trials.

Condé imagines her as the daughter of an enslaved woman and born as result of a rape. Tituba witnesses at an early age her mother’s hanging as punishment for resisting another rape attempt by a white man. After being orphaned, she flees the plantation and her role as young slave and lives as a maroon in the forests of Barbados. While living by herself she starts to learn about spiritual and healing practices from other women and is eventually recognized as a healer and a person in touch with the spirits herself, which gives her a certain amount of autonomy on the island. It is this knowledge and its anti-patriarchal spirituality which enables her throughout the novel to regain agency even in the most difficult and dire circumstances. The spiritual knowledge itself is only touched upon and is probably not transmittable through the written word anyway and Condé’s description of it is a reminder of how much is lost.

From the book I understood that the Women’s liberation movement in the sixties was not the first to discover or rediscover spirituality as a means to resist patriarchy. But thinking about what spirituality meant for the movement in the 1960s it seems that under capitalist market conditions, it can be turned into a commodity and effectively recuperated, eliminating much of its anti-patriarchal potential.

As a side note: The voice Condé uses throughout the book seems to me to be modelled after actual sources from the time period. It instills a sense of the time distance, and it sometimes makes it harder for me to empathise with the characters. This made me read the book less like a novel and more like source material which I appreciated.

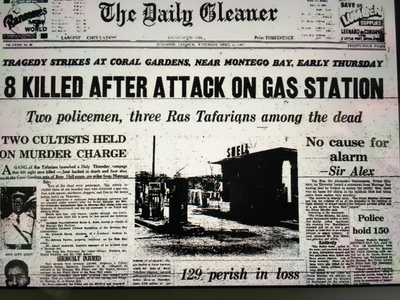

“Tituba, black witch of Salem” inspired me to look for other works by Caribbean authors and the next book I picked up was by Safiya Sinclair: How to say Babylon, a memoir. I did not particularly choose this book for topics of spirituality, but interestingly enough it connected well with my earlier reading. In it the author tells her life story growing up as the oldest daughter of a family that lived as Rastafarians. From its inception in the 1930s, the Rastafarian religion was persecuted by Jamaican authorities.

According to Saphiya Sinclair, it started as an egalitarian and non-hierarchical belief system centered on a communal lifestyle. However it was also very much patriarchal and assigned women inferior roles in its community. Incidentally this idea of women’s roles seems to be in part inspired by Christianity. Rastafarian religion was “designed” as a form of resistance against white supremacy and as such was not without value for Saphiya Sinclair while growing up. The hyper-patriarchal setting in her family and the isolation she was facing growing up due to the marginalization of Rastafarians in Jamaican society left her little choice but to resist both her father as absolute authority in her family and Rastafarian tenants in general. Her (and her sisters’) departure from Rastafarians beliefs eventually crystallizes in the act of cutting off her dread locks.

Saphiya Sinclair describes her resistance as rooted in a spirituality she developed through immersion into poetry. In this she’s helped greatly by her mother who valued education very highly and ensured she received the best education possible in spite of the family’s poverty. For Safiya Sinclair spirituality becomes the path and means to emancipation. In spite of the father’s at times very violent behavior towards her, she did seem to be able to embrace parts of her father’s spirituality and form it into a version that fit her own life choices. This was perhaps aided by the anti-hierarchical stance of Rastafarianism that helped her to see the spirituality as her father’s own and not that of a higher authority. Eventually, and after much struggle she’s able to transcend the misogynistic world view forced upon her by her father and even achieve a kind of reconciliation with him partly based on the realization that some of her father’s religious ideas are rooted in a resistance against an ideology of white supremacy.

As another side note, reading Saphiya Sinclair’s book made me realize once again how little I understand of poetry. It is an art form that for some reason so far has not really appealed to me even so both its sibling art forms prose and music do.

The third book I read was Diana McCauley’s A house for Pauline which tells the fictional story of a woman growing up in rural Jamaica in the 1920s who manages against the odds to educate herself and to find limited financial security by becoming a Ganja farmer. The experience of hurricane Charlie instills in her the wish to live in a house that can withstand such storms.

She manages to use the stones from the ruin of a nearby mansion that belonged to a slave owner to construct a house for her and her family. In her old age - she is nearly 100 years old when the book begins - the stones of her house begin to talk to her, leading her to unravel the history of the mansion which is inextricably interwoven with her own. While her childhood and young adulthood is mostly told without allusions to spirituality, the relationship to her house - at least in her old age - is described as spiritual. She hears it talking, she perceives it as part of herself and as embodiment of her history including the history of slavery she shares with most black Jamaicans. Tracking down the people she might have wronged when trying to secure her own future and when building her house becomes her primary motivation after hearing the stones of her house speak to her. This endeavour while entailing quite regular journeys also becomes a spiritual journey guided by a set of values that are both informed by her perception of history and by her sense of right and wrong. Apart from the speaking stones, the description of her sense of right and wrong was the most spiritual aspect of this book to me. Deprived of a regular education because of misogyny and patriarchy she nonetheless manages to develop a sense of justice far more complete and encompassing than what a Western education would have been able to offer.

As a final side note, I enjoyed how “A house for Pauline” played with my expectations as a reader. What seems like a setup for a fairy tale quest soon morphes into messy real-life trial and error undertakings whose outcomes were less and less predictable the longer I read on.

In conclusion I find it relevant that in all three books education and spirituality are interwoven with each other. For Tituba, education is learning about spirituality, for Safiya Sinclair formal education becomes a path to spirituality and for Pauline Sinclair, foregoing formal education while educating herself seems to enable spirituality. Spirituality - it seems - entails a rather steep learning curve, something that might be counterintuitive in a capitalist society promising instant gratification.

In addition, spirituality in all three books is portrayed as fundamentally anti-patriarchal, possibly even anti-hierarchical and as such seems almost like the precondition to emancipation. In my reading, it was spirituality that enabled the three protagonists to reframe themselves as something other than subjects and victims of male dominance and white supremacy. This of course begs the question what role spirituality would play in a liberated society. But - in view of the world right now - this question seems entirely academic.

One other aspect of the spirituality evident in these three books seems important to me. All three books describe very different forms and elements of spirituality, which are all very personal. And while the different forms of spirituality shape the struggles but also the solidarity of the protagonists, their spirituality itself is rarely the topic of their interactions, it tends to remain the medium.